- In between

: Review

Whence the Musical Avant-Garde in Buffalo?

During the course of this year's June in Buffalo (JIB) festival for new music at UB, audiences were reminded once again about how well Buffalo is regarded as one of the world's primary venues for new music. While this writer is accustomed to turning out articles devoted to the exciting but mostly standard repertoire performed by the Buffalo Philharmonic at Kleinhans, I could not help but find delight in the recollection of how Buffalo became so renowned for the flip-side of classical music - i.e. the music of the avant-garde. The tale of just how all this happened, and the creative spinoffs which ensued, makes for colorful telling. Oddly enough, it all began with the Buffalo Philharmonic back in 1963. At the time, the BPO had flourished artistically under the batons of two esteemed music directors revered for their Viennese approach to making music, namely William Steinberg, who was at the helm from 1945 through 1952, followed by Josef Krips, who presided over the Orchestra through the spring of 1963. Of course, when we say Viennese tradition we mean the heritage of Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler and Associates. (To be sure, in this context 'Viennese tradition' does not include names like Schönberg, Webern and Berg, who some argue were truly the world's first musical avant-gardists.)

But just then, at the point where the BPO was thinking about making its first major recordings (Krips had made a couple of pilot recordings with the BPO of Beethoven symphonies), suddenly there was a new wunderkind on the Buffalo block in the person of American composer, conductor and piano virtuoso Lukas Foss. German born, trained in France and the U.S., with a fine reputation for his keyboard legerdemain with Bach and Mozart, Foss was perfectly positioned as the BPO's new music director. Moreover, despite his reputed savvy for modern musical trends, just about everyone expected Foss to maintain the artistic esprit of his predecessors.

Then it happened - with a first stroke of creative lightning, the BPO would never be the same. Yes, Vienna was given its fair due - Foss' very first concert opened with Brahms' Symphony No.1. But there was a catch - after intermission the demure walls of Kleinhans shook for the first time with the sound of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring--and the audience loved it.

But that was merely a pre-echo of what would follow. Within just three seasons the Buffalo Philharmonic led the entire symphonic world in the performance of new music. Yet, to tell the whole truth, all was not rosy with more than a few BPO subscribers who simply loved the great masters. And there were more than a few sincere listeners who considered most of the 'modern stuff' to be written by musical impostors. However, because he was such a genuine item (the late Seymour Knox once referred to Foss as "...the only genius I ever met..."), Foss managed to maintain enough programming balance to keep the symphonic boat afloat, but a permanent sea change had surely prevailed over the great swells in Kleinhans - some called it a rip-tide.

With all of this we are not surprised that when the BPO did release its first three major recordings in 1967 (on Nonesuch), two of them were devoted to the music of the avant-garde (Xenakis, Cage, Pendercki, Foss), while the third was a splendid offering of Sibelius' Four Legends from Kalevala.

In retrospect, one would have naturally thought that the 'new-music-thing' for Buffalo would rest with the Philharmonic. Hardly. Foss had a lot more magic and mischief up his sleeve. To wit - by the fall of 1964 he had teamed-up with UB music department chairman Alan Sapp to convince both the Rockefeller Foundation and New York State to initiate and sponsor the Center for the Creative and Performing Arts on the UB campus.

In just one year the Foss-Sapp liaison had pulled off one of the greatest coups in the history of 20th century new music. The Center opened at UB in the fall of 1964 with nineteen full-time, non-teaching appointments of extraordinary young composers and instrumentalists from around the world. While the requisite high level of funding would prevail for just a few years, the Center nevertheless maintained its Evenings for New Music series at the Albright-Knox Gallery and at Carnegie Hall for more than a decade, in addition to making two European tours in the early 70s.

For those of us who were lucky enough to be en scène at the time, it is hard to believe that almost four decades have passed since those heady days in the early 60s. But when we consider just how quickly word about new music in Buffalo had spread around the world, we must also recognize thatthere was keen precedent in the international renown Buffalo already enjoyed in the world of modern art. To the point, the relatively small but highly esteemed collection at the Albright-Knox added direct credibility to Buffalo's burgeoning efforts in new music.

Yet, even with all of this, there was still more excitement to come. In 1975 the June in Buffalo festival for new music was initiated by one of the central figures of American contemporary music, Morton Feldman, who taught at UB from 1972 until his death in 1987. In spirit and intent, JIB was a direct spin-off from the Center. Since 1986, JIB has been directed by UB faculty composer David Felder, whose music and that of Feldman has been recently paired on a retrospective CD (see below). However, at one juncture there was a hiatus from the events of JIB, and Buffalo might have begun to slip from its position as a major player on the international new music scene. But the daylight was virtually saved in 1983 by the initiation of the North American New Music Festival (NAMF) at UB by the late yet still irrepressible Yvar Mikhashoff. With co-director Jan Williams, Mikhashoff presided over NAMF through 1993, a brilliant interval which again reflected the creative inertia of UB's Center for the Creative and Performing Arts of the 60s.

And the particular Buffalo Zeitgeist for new music remains vibrant to this very moment. This year's June in Buffalo festival at UB, held from June 3rd through the 8th, was yet again a very exciting affair, highlighted by the seminars and music of several top figures in the very broad world of new music. In addition to director David Felder, the invited resident composers for the event included Bernard Rands, Jonathon Harvey, Augusta Read Thomas, Philippe Manoury and John Harbison. Among a variety of fine soloists, the first-class performing ensembles for JIB included the Baird Trio (Stephen Manes, Movses Pogossian, Jonathon Golove), the New York New Music Ensemble, the Meridian Arts Ensemble, Quatuor Bozzini and the Slee Sinfonietta under the director of Magnus Mårtensson. It was a busy week indeed, comprising six composer lectures and eleven concert events at UB's Slee Hall and Baird Recital Hall.

Audience attendance at JIB this year seemed a fair cut above the normal turnout of new music loyalists (a.k.a. the 'usual suspects') whose presence has always been so vital to events of this kind. After all, a lot of the music heard was - well - 'out there' in one degree or another. And it is remarkable how discriminating these audiences can be. While it seems the wild and woolly days of rabid audience enthusiasm or censure (there used to be occasional hooting and audible jeering at new music concerts just a couple of decades ago) - audiences today express their pleasure, or relative boredom, with applause that ranks from polite acknowledgement to genuine enthusiasm, with curtain calls for deserved emphasis. In any case, the message gets through to the composers and performers, whether it matters to them or not (and it usually matters, very much).

With regard to the creative spinoffs which followed from Buffalo's musical avant-garde, a couple of points deserve highlighting. For one, the educational value has been very significant to the comprehensive mission of UB. To give just one example, the new music experience here has given rise to a solid graduate composition program at the University, with as many as twenty-five doctoral composition students from all over the world. Moreover, today there are perhaps dozens of important CD releases of new music by composers and performers who have been directly influenced, if not inspired, by an avant-garde experience here in Buffalo. Were it at a BPO concert at Kleinhans, at the Albright-Knox, or at UB, not to mention a variety of other important venues around town like Hallwalls and Rockwell Hall, Buffalo's musical avant-garde continues to make a big difference around the world.

A splendid example of Buffalo's avant-garde can be heard on a recent CD of orchestral music written by the past and present directors of June in Buffalo, namely Morton Feldman and David Felder. For devout new music buffs, this one is not to be missed. And for the classical music lovers out there whose hearts belong to the beautiful European traditions, have a listen to this latter world of music--it will be well worth the time.

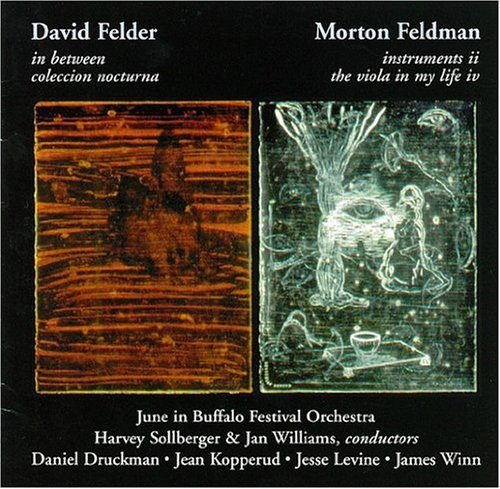

The Feldman/Felder CD was recorded at Slee Hall in June of 2000, which marked the 25th anniversary of JIB. The manifest contrast in composer styles could not be more acute - doubly fascinating in that it was Feldman who invited Felder, then fresh out of UC San Diego, to join the UB composition faculty in 1985. Released in 2001, the CD does not bear a title, though surely something like Buffalo en avant would have fit perfectly. Four works are 'fielded' here (in German, 'Feld' means 'field'), a pair by each composer: In Between (1999) and Coleccion Nocturna (1971) by David Felder, and The Viola in My Life IV (1971) and Instruments II (1975) by Morton Feldman.

In the CD's excellent liner notes, Buffalo composer Nils Vigeland observes: "In Between, for solo percussionist and chamber orchestra, is a work of eruptive force in which huge, pulsing blocks of sound hurtle through the entire orchestra. The In Between role of the soloist varies from that of concerto protagonist to just a prominent member of the orchestra." To this we must add bravissimo to soloist Daniel Druckman, on loan from the New York Philharmonic. The title page of Felder's Coleccion Nocturna provides the following notes by the composer: "Coleccion Nocturna is a large-scale set of five variations for clarinet/bass clarinet and piano soloists with orchestra and 4-channel magnetic tape. The inter-connected and overlapping segments develop gestural materials derived from the final six measures of this work into characteristic types evident in each section. Chilean poet-laureate Pablo Neruda's poem lent powerfully evocative images of a surreal nocturnal landscape, great distance, both physical and spiritual, and a world rich in energy and exhausted isolation." The outstanding soloists for the recording are clarinetist Jean Kopperud and pianist James Winn, both members of the New York New Music Ensemble. About the work, Vigeland remarks: "Coleccion Nocturna lives in an explosive world, offset by passages of quiet uncertainty."

A brief sample of Neruda's poetry offers a clue to Felder's powerful evocation:

I listen: for a dream of old playfellows,

and for women beloved, and I am

rent by the shock of my dreaming.

It is midnight all around me

and death beats on a gong like the sea.

As mentioned above, the Feldman pieces are in striking contrast to Felder's dynamic macrosonics. In both The Viola in My Life (inspired by violist Karen Phillips) and Instruments II, Feldman presents a kind of stasis of delicate, crystalline combinations of ever evolving orchestral timbres. Vigeland notes: "The Viola in My Life is one of Feldman's most diverse pieces, and the solo line carries the entire piece melodically on its shoulders. The complexity of the orchestral projection lies in the blending of an extremely varied combination of instruments which must speak as a single sound."

The soloist for The Viola in My Life is Jesse Levine, former principal violist of the BPO during the Foss years, currently on the faculty of Yale University. Mr. Levine's interpretation is simply exquisite, perfectly tuned and poetically phrased - sine qua non. Feldman's chamber work for eleven players, Instruments II, is also beautifully interpreted and recorded. Again, Feldman's intuition for ephemeral instrumental timbres is alluring, if not seductive - elegant and eloquent.

The June in Buffalo Festival Orchestra heard here turns in a fine effort. The Felder works are conducted by Harvey Solberger, who directs SONOR at UC San Diego and who has appeared frequently at JIB. The Feldman works are recorded under the baton of percussionist extraordinaire Jan Williams, a former member and director of the Center for the Creative and performing Arts, and professor of percussion at UB. In sum, the CD is a handsome witness to Buffalo's new music heritage. The recording is available on the EMF label of the Electronic Music Foundation.